Patricia Niehaus is national president of the Federal Managers Association and chief of labor and employee relations at Travis Air Force Base.

The various iterations of Civil Service Reform beginning in the late 1800s were written to preclude the very problem currently facing federal employees: political figures wanting to influence the careers of civil servants. Politics should not have a role in the retention or separation of a civil servant.

If the federal civil service is to be the model employer that we should be, managers should continue to be required to provide justification and evidence to support disciplinary and performance actions taken against employees.

That does not mean that every employee should be retained. As with any population, there are good employees and bad employees and employees who just aren't suited to the position they occupy. As managers, we have an obligation to ensure that we're terminating employees for the right reasons—unacceptable conduct or performance that cannot be corrected any other way.

The current system, as written in the statute, isn't broken. It just isn't being used as it was written. The statute only requires a minimum 30 day notice period from the date the proposal to remove or demote is issued to the employee to the effective date of action. That is not an unreasonable period of time to decide whether or not to terminate an individual's employment. While disciplinary actions should not be taken based on suspicions or assumptions without supporting evidence, it certainly should not take two years to complete an investigation and determine whether or not there is sufficient evidence to remove a federal employee.

Performance cases generally do take longer than disciplinary ones. The reason for that is the requirement under 5 CFR 432 to provide the employee with an opportunity to improve. In many agencies, there is a practice of allowing at least 90 days of supervision before an employee is appraised and it logically follows that this is often the minimum period to allow employees to demonstrate they have improved to an acceptable level of performance. This is faster and less costly than recruiting for a replacement if the employee is able to improve. Once the improvement period is completed and the employee is determined not to have improved his or her performance to an acceptable level, the same notice requirement applies to the performance action as to disciplinary actions.

Congress should exercise caution when thinking about enacting legislation that imposes arbitrary time limits on taking actions. We often hear from frustrated managers that they can't get removals approved through their legal offices because they must deal with agency attorneys who are more concerned with risk avoidance than risk management. Setting a specific number of days to process an action may result in findings of legal insufficiency and no action being taken rather than taking time to resolve any documentary issues.

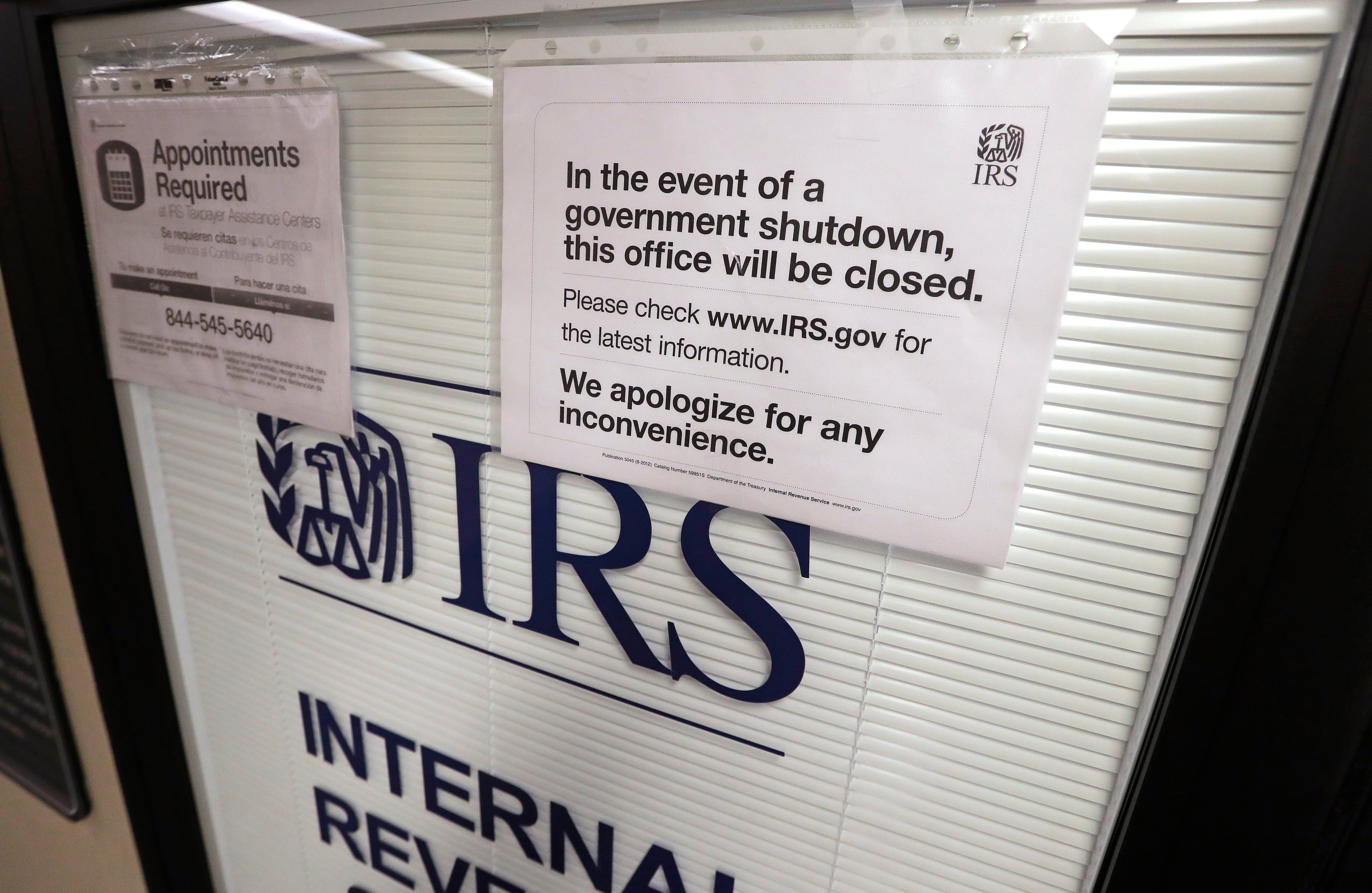

There is also a possible unintended consequence: making civil service even less attractive than it already is. After service to country, many civil servants cite one of the main attractions of civil service is job security. Many civil service employees endure salaries well below what they could command in the private sector, pay freezes, furloughs, and other adverse impacts of politics because they know they cannot be fired on a whim as they can in many private sector jobs. Of course, with sequestration and furloughs, that comfort level has largely been diminished.

If we truly want to attract and retain the best and the brightest, we need to make civil service MORE attractive—not less. The model employer of the future should have a more current and flexible classification and pay system than the 65-year old General Schedule. Pay for performance should be an integral part of federal service, and employees should be protected from unreasonable actions.