ST. LOUIS — Ben Phillips’ childhood memories include basketball games with friends, and neighbors gathering in the summer shade at their St. Louis housing complex. He also remembers watching men in hazmat suits scurry on the roofs of high-rise buildings as a dense material poured into the air.

“I remember the mist,” Phillips, now 73, said. “I remember what we thought was smoke rising out of the chimneys. Then there were machines on top of the buildings that were spewing this mist.”

As Congress considers payments to victims of Cold War-era nuclear contamination in the St. Louis region, people who were targeted for secret government testing from that same time period believe they’re due compensation, too.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Army used blowers on top of buildings and in the backs of station wagons to spray a potential carcinogen into the air surrounding a St. Louis housing project where most residents were Black. The government contends the zinc cadmium sulfide sprayed to simulate what would happen in a biological weapons attack was harmless.

Phillips and Chester Deanes disagree. The men who grew up at the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex are now leading the charge seeking compensation and further health studies that could determine whether the secretive testing contributed to various illnesses or premature deaths that some Pruitt-Igoe residents later suffered.

“We were experimented on,” Phillips said. “That was a plan. And it wasn’t an accident.”

The new push comes as federal lawmakers are weighing compensation for people claiming harm from other government actions — and inactions — during the Cold War.

The Associated Press reported in July that the government and companies responsible for nuclear bomb production and atomic waste storage sites in and near St. Louis were aware of health risks, spills and other problems, but often ignored them. Many believe the nuclear waste was responsible for the deaths of loved ones and ongoing health problems.

The AP report, part of a collaboration with The Missouri Independent and the nonprofit newsroom MuckRock, examined documents obtained by outside researchers through the Freedom of Information Act.

Republican U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley introduced legislation soon after the news reports calling for expansion of an existing compensation program for exposure victims. The Senate endorsed the amendment. While the House has yet to vote, Democratic President Joe Biden said last month that he was “prepared to help in terms of making sure that those folks are taken care of.”

Former residents of Pruitt-Igoe say they should be taken care of, too.

Phillips and Deanes, 75, are co-founders of PHACTS, which stands for Pruitt-Igoe Historical Accounting, Compensation, and Truth Seeking. Their attorney, Elkin Kistner, said it would be “appropriate and necessary” for Hawley’s proposal to be widened to include former Pruitt-Igoe residents.

The government released documents in 1994 revealing details about the spraying. And St. Louis wasn’t alone in being subjected to secretive Cold War-era testing. Similar spraying occurred at nearly three dozen other locations.

There were other types of secret testing. In a 2017 book, St. Louis sociologist Lisa Martino-Taylor cited documents obtained through a FOIA request to detail how pregnant women in several cities were given doses of radioactive iron during prenatal visits to determine how much was absorbed into the blood of the mothers and babies. The government also created radiation fields inside buildings, including a California high school.

The area of the testing in St. Louis was described in Army documents as “a densely populated slum district.” About three-quarters of the residents were Black.

“We were living in so-called poverty,” Deanes said. “That’s why they did it. They have been experimenting on those living on the edge since I’ve known America. And of course they could get away with it because they didn’t tell anyone.”

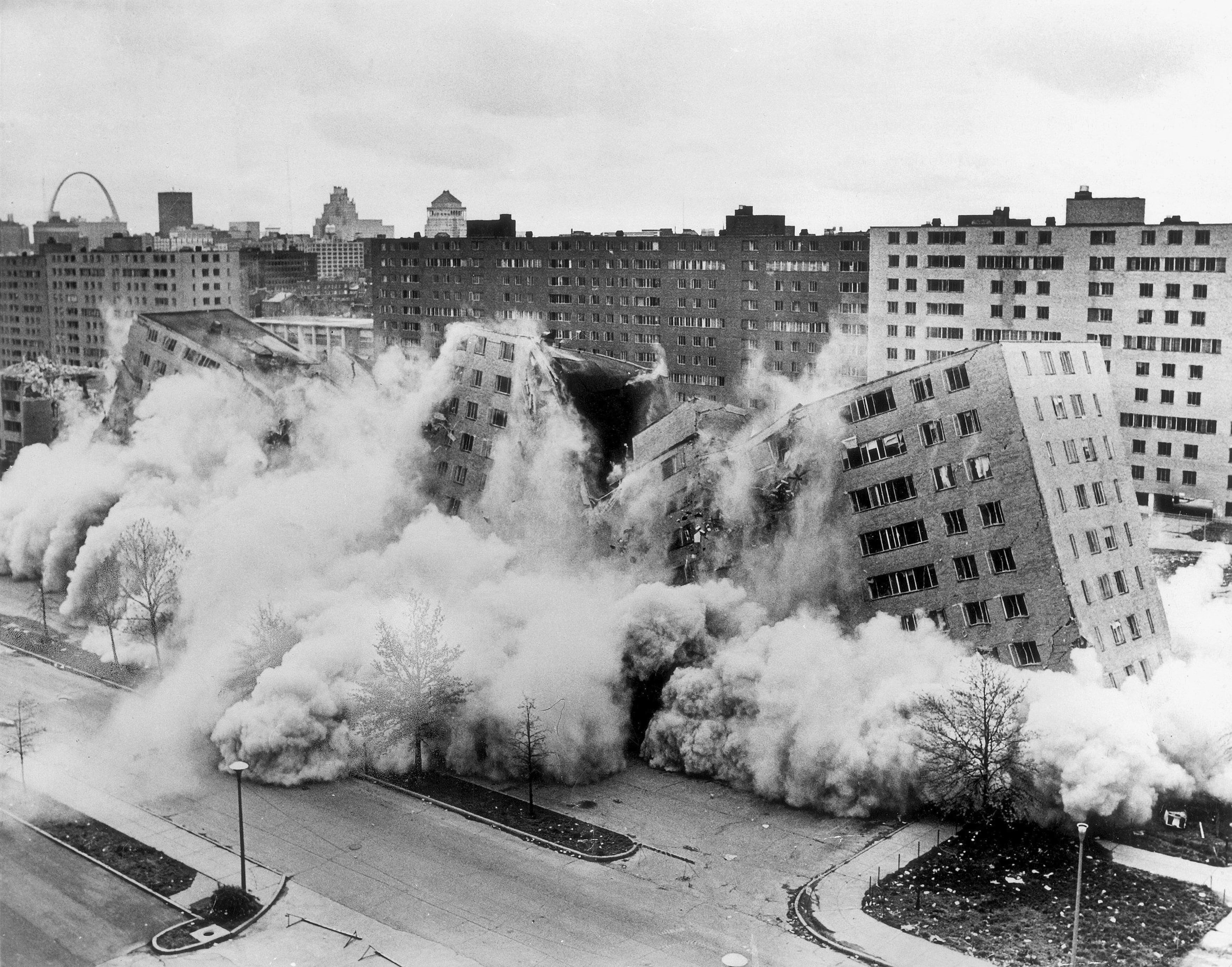

Pruitt-Igoe was built in the 1950s with the promise of a new and better life for lower income residents. The project failed and was demolished in the 1970s.

Despite the ultimate demise, Deanes and Phillips said that through their youth, Pruitt-Igoe was a welcoming place. Yet over the years, both men cited countless premature deaths and unusual illnesses among relatives and friends who once lived at Pruitt-Igoe.

Phillips’ mother died of cancer and a sister suffered from convulsions that puzzled her doctors, he said. Phillips himself lost hearing in one ear due to a benign tumor. Deanes’ brother battled health problems for years and died of heart failure.

Both men wonder if the spraying was responsible.

A government study found that in a worst-case scenario, “repeated exposures to zinc cadmium sulfide could cause kidney and bone toxicity and lung cancer.” Yet the Army contends there is no evidence anyone in St. Louis was harmed.

A spokesperson for the Army said in a statement to the AP that health assessments performed by the Army “concluded that exposure would not pose a health risk,” and follow-up independent studies also found no cause for alarm.

Phillips and Deane believe the previous health studies were half-hearted. In addition to a new health study, they’d like to see soil tested to see if any radioactive material was part of the spraying.

It’s unclear if Hawley’s bill might be expanded. Messages left with his office were not returned.

Democratic U.S. Rep. Cori Bush of St. Louis said in a statement that she and her staff “are currently looking into alternative pathways that the federal government can take to ensure those impacted by the spraying of radioactive compounds and biochemicals in Pruitt-Igoe are also addressed.”

Deanes and Phillips say that in addition to compensation and more detailed studies, they want an apology.

“This shouldn’t go on,” Deanes said. “How are we supposed to be the leader of the free world and this is the way we conduct ourselves with our own citizens?”