As part of its examination of the presidential transition, The Partnership for Public Service gathered some of Washington's national security experts to talk about what awaits the next administration.

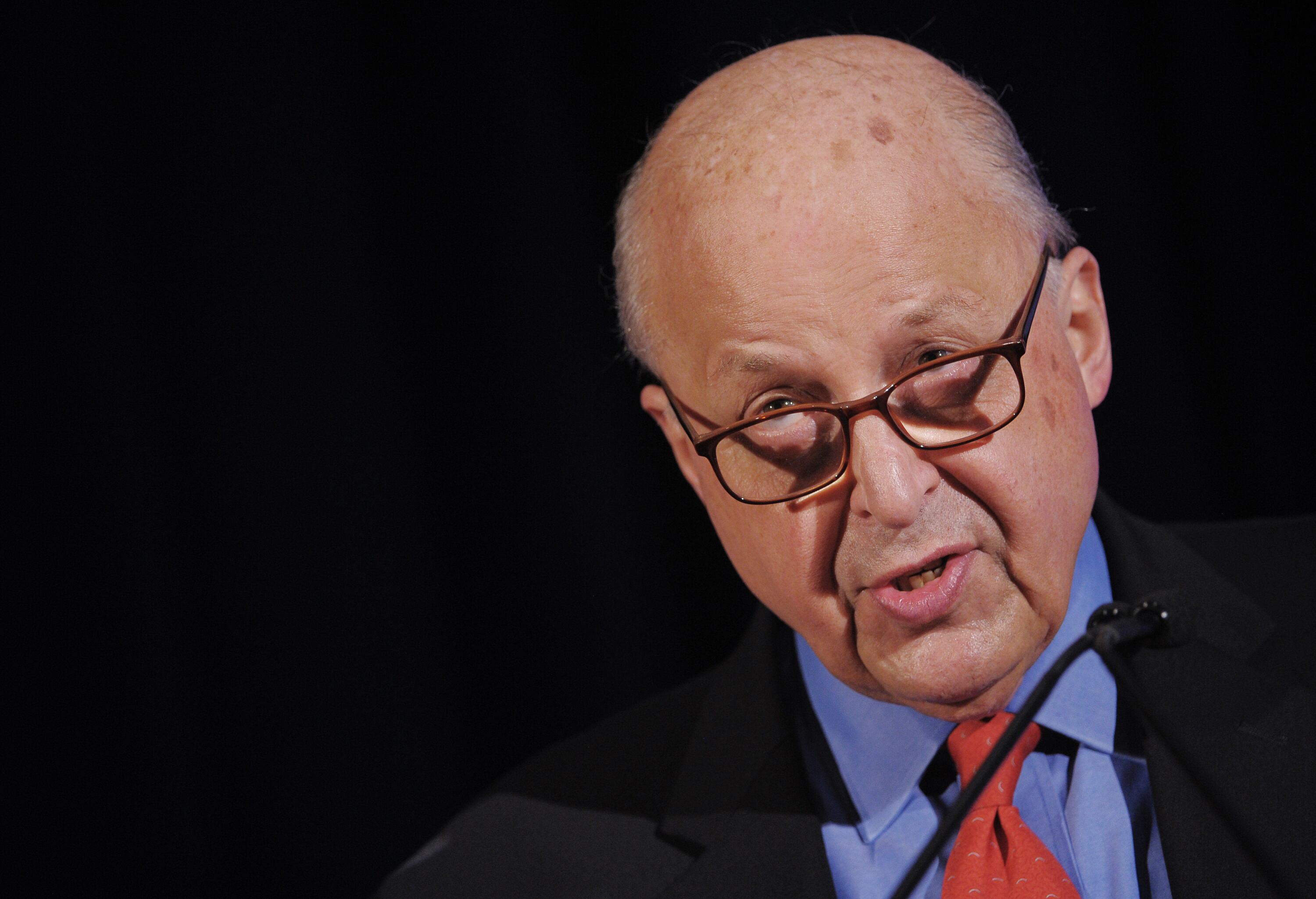

With the 2017 inauguration presenting a vulnerable moment for the nation, former Director of National Intelligence John Negroponte, former National Security Adviser Stephen Hadley, former Rep. Jane Harman, D-Calif., and former Undersecretary of Defense for policy Michèle Flournoy weighed everything from how to work with Congress to who should be on the National Security Council.

Among the highlights were:

- Here comes the new boss, work with the old boss

For whoever gets elected, one of the most important aspects of the transition will be ensuring their team works with the Obama administration to manage national security threats before and during the inauguration.

One red letter example of what has worked well in terms of inaugurations is 2008.

"The George W. Bush administration and the incoming Obama administration is a very good illustration of how a lot depends on the incoming administration," said Negroponte.

"The incumbent has a great responsibility in this process, it's not only the winners of the election."

Hadley, who was part of the transition as Bush's national security advisor, said the outgoing administration made a point of cooperating with the Obama team to ensure there was no lag in national security as a result of the handover.

"We told all of the members of the [National Security Council] staff to make copies of the documents that they or the new team would need for the incoming administration," he said. "While the senior directors all left, the directors stayed in place and one was appointed as 'acting', so the new team had a workforce and the papers they needed do the business of government."

Hadley added that the Bush team also had memos outlining the work the previous NSC had done on the major issues facing it, the progress of that work and any recommendations it had.

In addition, he said the administrations did "side-by-side walk-throughs" on how to manage a national security crisis to ensure the transition was a smooth one.

"I think most people thought it was a good transition, and one of the things [The Partnership has] done is to take that and try to move it to the next level."

- Work with Congress to smooth confirmation

One of the biggest hurdles for a new administration is getting its cabinet and leadership confirmed.

The Partnership estimated that a quarter of the 4,000 presidential appointments will require Senate confirmation, and such confirmation is often used as a political bargaining chip.

That's a bad idea, said Harman, and the next administration has got to come to a kumbaya-moment with Congress to ensure that it has the ability to govern.

"I don't really think it's on the level, the confirmation process," she said. "It's a weapon of mass destruction. It is enormously harmful and it didn't use to be that way."

Hadley agreed, saying that the confirmation process needs some tweaking, including moving the paper process online and having the candidates submit possible appointees for background checks now.

"The candidates need to get a list of 100 people from whom they may make senior appointments and get them all cleared," he said. "[There needs to be] a commitment to move it fast without hostages.

"When [former Sens.] Sam Nunn and John Warner ran the Senate Armed Services Committee, they would basically say, 'When I get all of the [paper work], we will get it through the committee and to the floor in one week.' So it can be done."

- Define role clarity for the cabinet

One of the broader issues of national security of late has been the consolidation of policy control within the White House.

Flournoy—who served during Obama's first term—said one way to ensure smoother policy applications was through a practice called "role clarity," where the president spells out his expectations for the roles cabinet secretaries will play in administration strategy.

"I think the [National Security Councils] that worked best was when the National Security Advisor really saw himself first as a sort of systems administrator," she said, "running a process that would ensure the full range of views and options, including dissent, would get to a president so the president could make better decisions."

Flournoy said the National Security Advisor must then execute decisions with clear limits and empower the people that have to carry it out.

To hear more about The Partnership for Public Service's presidential transition series, Ready To Govern, visit its website.