Jack Kaye used to wear ties to kindergarten.

So it’s perhaps no surprise that the NASA scientist has about 50 ties to this day. Some he’s had for a long time. Others don’t make it into his rotation very often, less so these days since he can telework a few times a week.

“Scientists are not known for their fashion sense,” he said in an interview sharing his personal observations about federal fashion. “From a public facing point of view ... it’s almost like we’re encouraged not to be too dressy. It’s a way of connecting with audiences.”

Kaye doesn’t mind wearing ties, but he has welcomed other changes that allow him to wear sneakers instead of dress shoes, lightweight cotton pants instead of dry-clean-only slacks, and short sleeve shirts in summer with a sport coat. Besides, the coat is as much for pockets as anything, he said.

Other federal employees are not nearly as pro-tie, going so far as to call them “little strips of fabric dangling from necks,” according to results from a Federal Times survey of about 600 government employees from three dozen agencies who responded to questions about what they wear to work.

As the White House faces calls to bring federal employees back to government office buildings, many are wondering if the old rules about how to dress for the office still apply, or if the rise in casual attire that came with working from home will continue to rule. Almost all agencies allowed some level of telework pre-pandemic. Now, with reentry at various stages in government, it begs the question, and readers answered: will workplace attire revert to the old rules if telework does?

“It will never go back to the way it was before COVID,” said Kevin Kampschroer, an employee of the General Services Administration. “The only prediction I’m willing to be absolutely certain about is it will not be the same.”

Telework and dressing down

Most survey respondents identified as male, had more than 20 years of federal government experience and worked in a defense-related agency. The remainder was scattered among independent agencies in the capital region and across the country.

According to the survey results, the general consensus was that workplace dress in federal agencies has relaxed, if it even changed at all. Very few respondents said that dress codes became more formal in the last few years. A few also said that society has been trending more casual for years; telework may just have accelerated it.

Common articles of clothing that feds reported wearing included polos, khakis, sport coats, comfortable shoes and blouses.

Still, the D.C. area has long been stylishly conservative when compared to Fashion Week host cities such as New York or Los Angeles.

“Here you see more people wearing more of a camel, the grays, the blacks, the whites — kind of tempered down colors,” said Susan Kyles, director of Dress for Success in Washington D.C., an organization that provides women with high-quality suits and professional workwear in preparation for their first job or interview.

What she and her team of stylists prescribe clients hasn’t changed much, she said, though during times of virtual interviews, a polished blouse became “the whole suit” for clients. Organizations like hers even found themselves with surpluses of suits during the pandemic as many teleworking employees were donating clothes that were collecting dust.

Social norms have kept the federal dress code relatively intact in the absence of an official, government-sponsored dress code led by the White House or any other agency. That would be challenging to enjoin, given how many different jobs are held by the 2-million large civil service.

And in many cases, survey respondents said how they dress is less about personal preference and more about dressing for function.

At the Forest Service, Environmental Protection Agency or Food Safety and Inspection Service, workwear is a matter of safety for employees who need helmets, hairnets, waders or pants and shirts festooned with pockets to do their jobs. Agency heads who orate before a televised audience of millions and represent the heritage of U.S. policy must dress for the part, including a de rigueur flag pin on their crisp lapels. Uniforms for military service members show cohesion and identify experts or the person in charge without having to say a word.

How did things change?

Of those whose said their dress code has changed, most respondents said it became more casual — by a lot or just a little. About 46% said their agencies still have a dress code and 12% said they had one even while in virtual meetings.

Respondents indicated that dress codes where more akin to unenforced guidance as opposed to mandatory rules.

Eric, a civilian employee who did not use his last name for privacy concerns, works in an agency where he can wear khakis or 5.11 Tactical pants with a collared shirt, be it a polo or dress shirt, tucked or untucked.

“But if we are meeting anybody external to our agency or we’re meeting with anybody in the front office, it’s definitely coat and tie,” he said in an interview. “It’s not formalized in any sort of document. It’s just institutional knowledge that that’s the deal.”

The Society for Human Resource Managers sums up where this idea comes from: “Employees typically are the ‘face’ of the company, and employers often find it necessary to control that image.”

Survey respondents like Eric echoed this idea, saying that they set dressier standards for themselves when meeting with high-ranking officials or interfacing with the public.

The State Department, for example, has a mission that it says must reflect professionalism at home and abroad, so its employees should dress in a way that honors that and protects them. Unions have also negotiated their own agreements.

Image 0 of 16

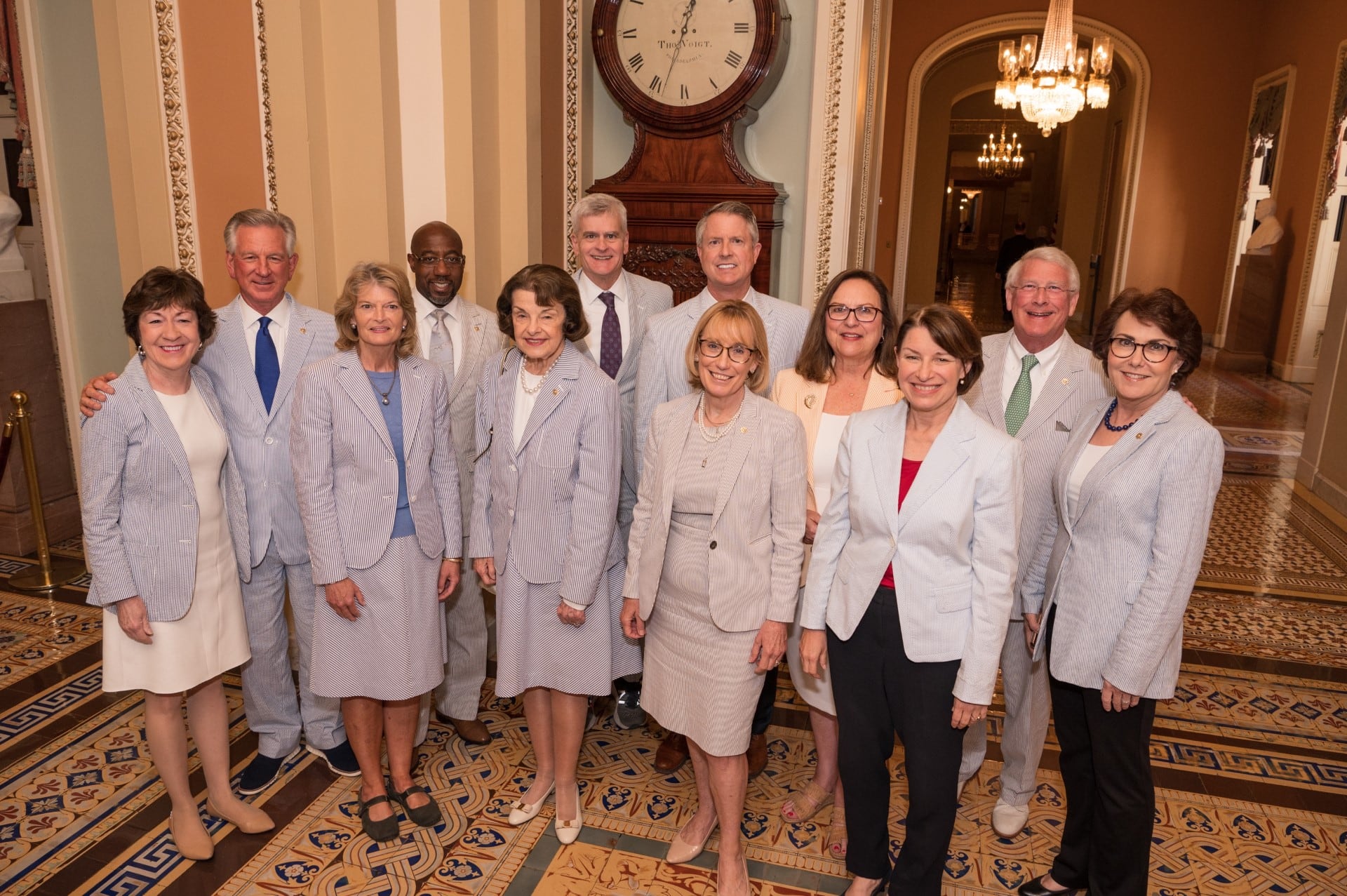

Congress offers a more predictable contrast, whereby committee hearings and official business of the chambers are still conducted in traditional business attire. In the sea of neutral tones and pinstripes, a few colorful personal choices have bobbed up. Women can be seen today wearing colorful suit pants and bright prints, and men frequently wear dress shoes with white, rubber soles that don’t click on the worn stone floors of the Capitol. And if you happen to walk into the Capitol on June 8, you’ll find lawmakers ditching their polyester for seersucker, per this senator’s tradition.

RELATED

When fashion deviates from the muted norms, people take note.

The Associated Press debunked a rumor that Maryland Rep. Jamie Raskin was required by House Republicans to remove the bandana he was wearing on his head while undergoing chemotherapy treatment for a lymphoma diagnosis he received last year.

In 2017, then-House Speaker Paul Ryan said he would modernize the House dress code, especially with respect to the hot summer months and customary requirements for coats and sleeves, Politico reported.

A year later, Rep. Ilhan Omar, a democrat from Minnesota and one of two Muslim-American women elected to Congress, led Congress to a vote lifting a 181-year ban on headwear for lawmakers.

Just this month, a Breitbart reporter tweeted criticism over a photo of Sen. John Fetterman wearing athletic clothes.

“We will always see Congress demanding a degree of formality,” said Michael Suchecki, a spokesperson for the Congressional Progressive Staff Association. “I think that’s appropriate; it’s just that as the times change, so must what that looks like.”

Many would agree that dress codes may serve a purpose. After all, as Robin Givhan, the award-winning fashion writer for The Washington Post, said: when it comes to politicians’ dress, the public expects a certain decorum.

“... Most people want their representative to represent them in a way that is very polished, that they walk into Congress with a certain amount of respect and perhaps even a little bit of awe,” Givhan told NPR in 2011. “And a lot of that comes through in what they choose to wear.”

Still, Suchecki said formality doesn’t have to mean uniformity. Embracing a more inclusive dress code would would reduce the cost burden of an expensive wardrobe for low-income staff, establish less restrictive expectations for women and non-binary staff, and highlight the colors, patterns and styles of a cultured workforce instead of graying them out, he added.

“Assume the culture is less relaxed than you would hope it is,” he added when asked for wardrobe advice he would give to young people starting a job on the Hill. “Assume that you have less freedom there.”

And if employees do see an office choosing to be more accepting of the backgrounds and diversity of their staff, then maybe on day two, they can adjust for it, he said.

What do feds want?

Respondents in the survey were divided on whether a dress code, of any kind, is appropriate or useful.

Some said that standards have become too lax and irreverent of the soul of public service and urged stricter requirements.

“Many more slobs and sloths,” said a respondent.

“If you’re getting GS-15 pay, you really should wear socks,” said another.

“To attract the younger generation, a more comfortable, relaxed dress code is needed,” said one respondent. “Gen Z and forward, and some late Gen-Xers, simply won’t tolerate the formal dress codes. Our leaders need to be stronger in enforcing a ‘no bar-clothes’ culture to prevent those who will abuse a more relaxed dress code, thus ruining it for the rest of us.”

Others said it was time the government recognized that productivity could be achieved with and without a starched collar. Having personal discretion based on weather, level of public-facing activity and amount of remote work is appreciated to cut down on expenses, they noted.

Only 7% of the full-time federal workforce is younger than 30, and recruitment troubles have deepened the cultural differences between private and public sector work.

Respondents did generally agree on one thing: however agencies dictate their expectations for dress, make expectations clear and communicate them throughout the ranks.

And as for Kaye, when he finds himself dressing for an important meeting, it’s a nice excuse to break out a tie that features the Keeling Curve for carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere and the formulas for the leading green greenhouse gases — a favorite, he said.

“If I have an oceans meeting, I’ll wear a fish tie,” he added. “If [it’s] snowing, I have a snowflake tie. If we’re dealing with methane, I have a tie with cows on it.”

Molly Weisner is a staff reporter for Federal Times where she covers labor, policy and contracting pertaining to the government workforce. She made previous stops at USA Today and McClatchy as a digital producer, and worked at The New York Times as a copy editor. Molly majored in journalism at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.