Many federal employees in need of infertility treatments have been on the hook for medical bills for procedures not covered by government health insurers. And for decades, reproductive health care has been a hushed topic and misunderstood about how it works.

That discourse is changing, say health experts who have been watching the government’s response to industry and states that are moving to offer more options for infertility in employee benefit plans. This month, the White House’s Office of Personnel Management revealed it will be requiring — not just encouraging — providers of federal insurance to expand coverage for common infertility procedures and be more clear about what they’re offering.

For some federal employees, like Heather Peterson, who rely on infertility treatments, that means “everything.”

“It’s not just the government; there’s just generally not fertility coverage,” she said in an interview. “I’m grateful that it’s even a conversation ... It’s heartening. It feels like there’s movement.”

RELATED

For her and other federal employees, infertility costs are a big expense, even with health insurance. The FEHB program has been criticized by some for its spotty and minimal infertility coverage, while states and large companies have moved to cover more.

Roughly 40% of large U.S. employers offer coverage for IVF treatment and as of 2022, 20 states have passed fertility insurance coverage laws, 14 of which specifically include IVF.

OPM said it has been monitoring these efforts in its annual letter to federal health insurance providers on March 1, recognizing that “there continues to be a steady, upward trend among large employers in offering various coverage options for Assisted Reproductive Technology.”

Roughly 8 million people get health insurance through the FEHB program, a government-run marketplace of more than 270 plans overseen by the OPM. Each year, the Office writes to insurance companies to set goals for the program and make requirements and suggestions to achieve them. In the last year, employee groups and members of Congress have urged the Biden administration to push harder for comprehensive infertility coverage as one way to better recruit and retain.

What’s new for 2024

For 2024, FEHB carriers will now be required to provide coverage for artificial insemination procedures and associated drugs. That does not include a requirement to cover donor sperm.

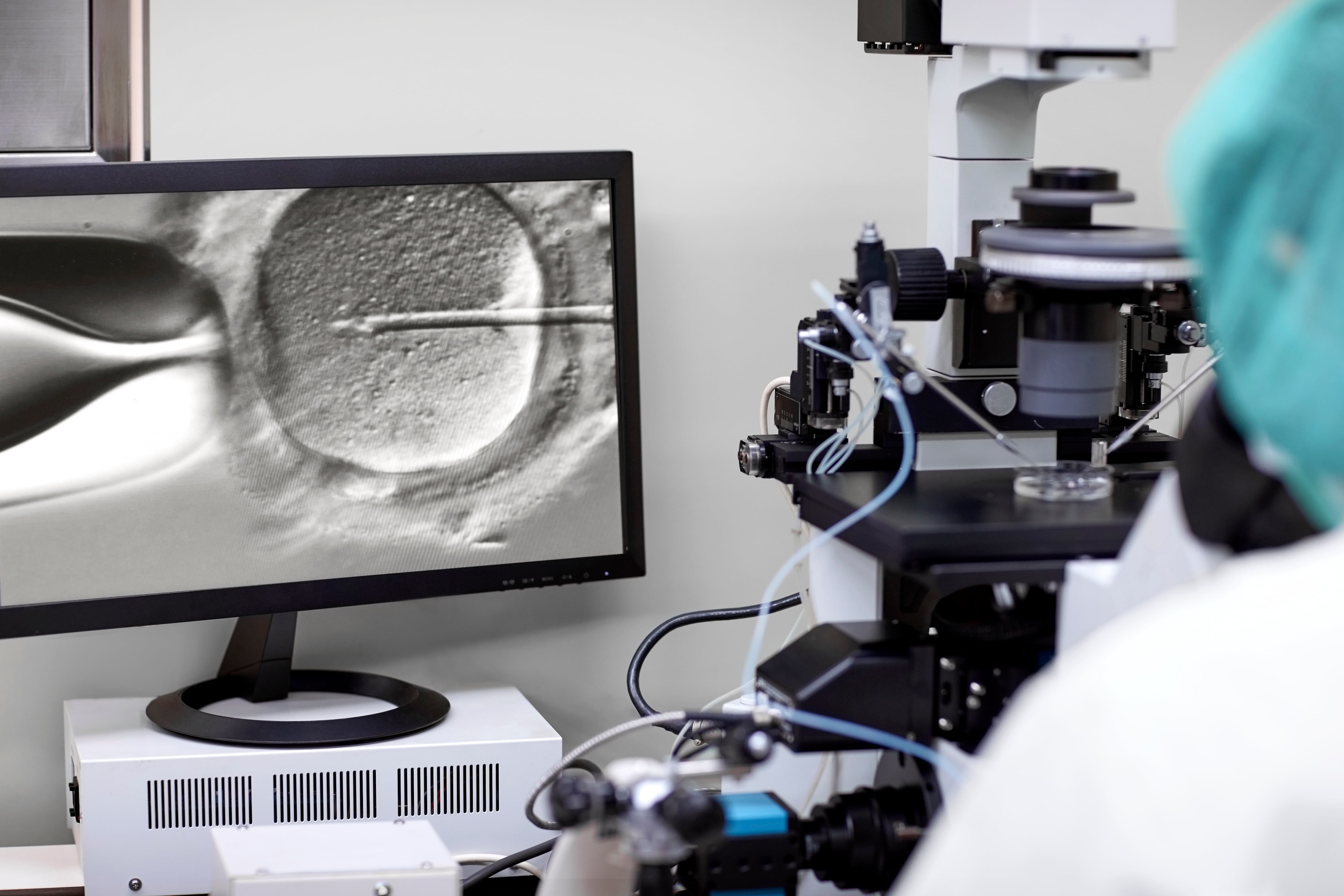

Artificial insemination doesn’t work for everyone, though, so to help with patients who are left with IVF, OPM is also requiring carriers to cover medications for three cycles per year. IVF drugs alone can cost several thousand dollars.

“I don’t want to understate the significance of that policy change — thousands of federal employees would benefit from that,” said Sean Tipton, chief advocacy and policy officer of American Society for Reproductive Medicine, in an interview. “On the other hand, I’m not sure why they stopped at just IVF drugs.”

Health policy experts applauded OPM for doubling down on support for infertility coverage this year while cautioning that gaps remain. Kevin Moss of Consumers’ Checkbook said that there are still substantial out-of-pocket costs that families will face from the cost sharing arrangements and from services that are not required to be covered.

“We’re a little disappointed that [for] the IVF benefit, that all they’re gonna require is the cost of medication,” Tipton added. “There’re doctors, there’s physician time, there’re laboratory costs. And those can be significant.”

To be clear on who and what is covered, OPM is also requiring insurers to define infertility and clearly explain who qualifies in brochures and online.

When Peterson was electing her benefits as a newly minted federal employee, she said she remembers Googling infertility options and not being clear about what would apply to her or not.

“There’s paralysis of choice because the government, on the one hand, offers you so many options, but on the other hand, it can be confusing trying to compare them,” she said.

In the past, there have been coverage differences based on diagnosis that some federal employees have said is misleading. For example, last year’s carrier letter focused on expanded benefits for iatrogenic infertility, which represents a portion of all women who may need treatment.

An OPM spokesperson confirmed to Federal Times that the new requirements are not limited to iatrogenic cases.

Why does coverage lack?

Fully comprehensive infertility coverage is still the goal for many federal employees and health advocates, and while there have been incremental steps toward that, coverage still lacks.

IVF in particular seems to a lingering holdout, experts said, as it has taken time for the discourse to recognize that it is not experimental or extreme, but medically necessary for certain patients.

There are also vestigial political barriers around women’s health in general. Following the overturning of abortion protections established by Roe v. Wade, some may also question whether a fertilized egg has “personhood protections” and thus scrutinize choices to discard, store or move embryos.

“If the characterization of embryos is such that they are conferred personhood status, it’s going to put a chill on offering IVF,” said Joyce Reinecke, executive director of the Alliance for Fertility Preservation.

The other issue is that OPM must negotiate plans on behalf of all 2.1 million civilian employees, many of which may be closer to retirement than they are to starting a family, Federal Times previously reported.

“The absence of even one nationwide FEHB plan providing ART services results in far too many civil servants being denied access to infertility services,” said a March 10 letter to OPM signed by lawmakers and provided to Federal Times. “In addition, the 19 regional FEHB plan options that do offer some level of ART coverage vary greatly in terms of what specific services are included, resulting in a confusing and complex patchwork of infertility coverage that is inequitably distributed and difficult to navigate.”

Bottom line: for federal employees who need simpler medical interventions to start a family, like ovulation induction drugs or insemination, those are likely to be covered in plan year 2024. If they are in need of more complicated treatments like IVF, more of those costs may be covered now than before, but a lot will remain out-of-pocket.

“If you’re a federal employee, and you require IVF to build your family, you are going to be better off because of this change in policy, but you are still going to have to part with a significant amount of money,” Tipton said.

Employees will have to wait until OPM completes benefit negotiations this summer to see how costs and actual plans shake out. Reinecke said she doesn’t think this means that premiums must automatically skyrocket. Some studies that indicate infertility coverage mandates at the state level minimally impacted premiums.

“I don’t think infertility treatments are any more expensive than some other services that we’ve deemed medically necessary, and we don’t query,” she said. ”There’s an inherent value judgment there.”

When is open season for 2024?

Federal regulations say open season will be held each year from the Monday of the second full work week in November through the Monday of the second full workweek in December.

That means for 2024, open season is slated for Nov. 13 to Dec. 11, 2023.

OPM expects to complete benefit negotiations by July 31 and rate negotiations by mid-August to prepare for a timely open season.

Molly Weisner is a staff reporter for Federal Times where she covers labor, policy and contracting pertaining to the government workforce. She made previous stops at USA Today and McClatchy as a digital producer, and worked at The New York Times as a copy editor. Molly majored in journalism at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.