The head of the Federal Labor Relations Authority said that after two decades of stagnant budgets, staffing cuts and long-term vacancies, anything less than the full $33 million requested in the fiscal 2024 budget will debilitate the independent agency that oversees union relationships within government.

In an interview with Federal Times, FLRA Chair Susan Tsui Grundmann said her agency has had to eliminate nearly all travel, consolidate floors in its building and look at cutting bonuses and training to make up for recent budgets that haven’t increased in 20 years. The FY24 request is a 14% increase over last year, and it’s also five months late. The fiscal year began Oct. 1.

“The well is dry,” Grundmann, a Biden nominee, said. “There’s no meat left on the bone. We can’t give anymore.”

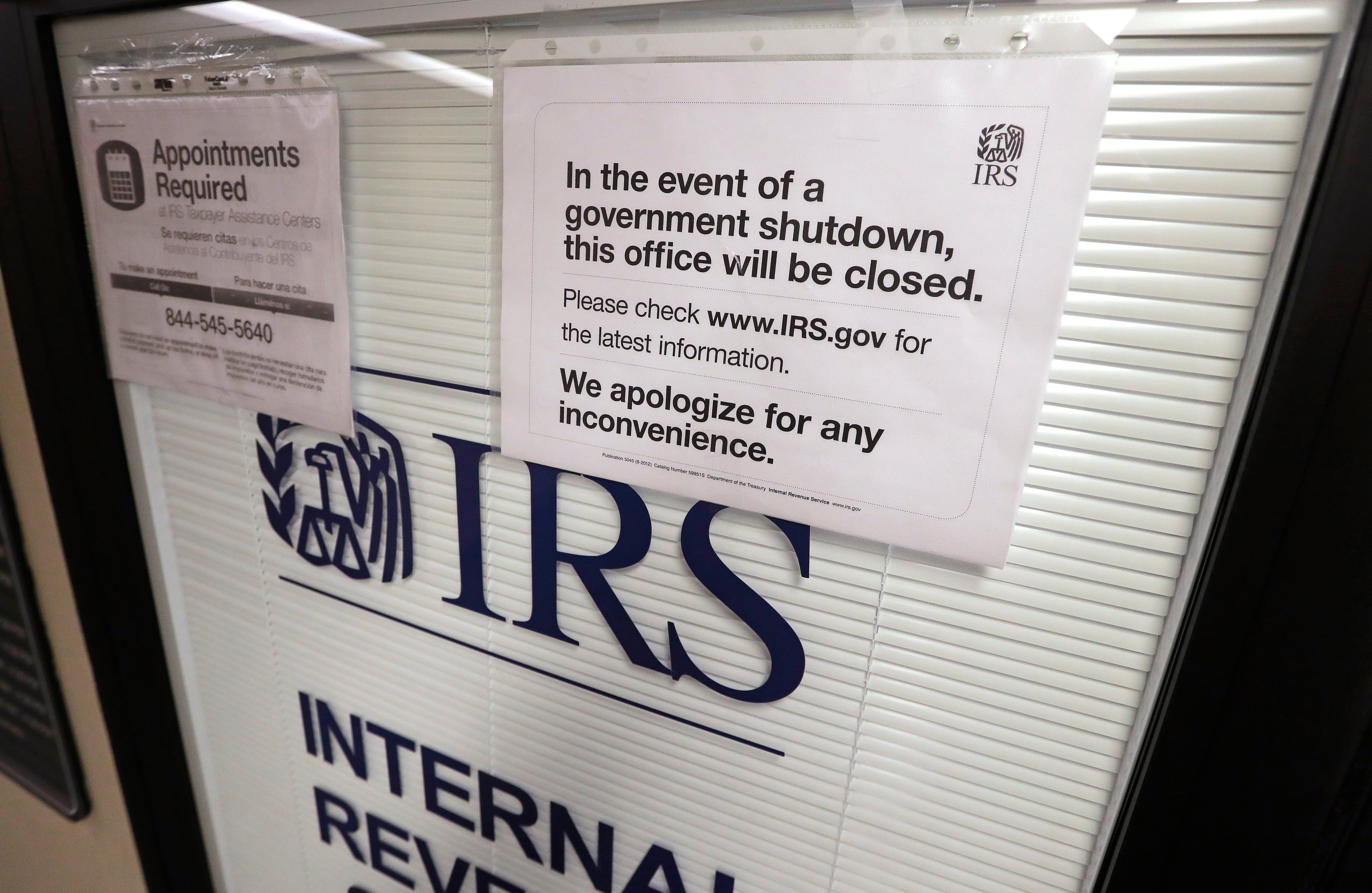

The FLRA is funded by the Financial Services-General Government spending bill, one of 12 total bills that includes spending for two dozen separate agencies, from the U.S. Treasury to White House offices. So far this fiscal year, these agencies, among others, have been running on a series of continuing resolutions, the latest of which is set to expire on March 22. After Congress avoided a partial government shutdown on March 8 by passing the first group of appropriations bills, lawmakers are feverishly working this week to vote on the remaining ones by Friday.

RELATED

On Tuesday, Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., said on X, formerly known as Twitter, that the House and Senate have begun drafting bill text to be prepared for consideration “as soon as possible.” The White House released a statement the same day saying President Joe Biden would sign the deal “right away.”

Though resolution seems imminent, it’s not clear what it will entail. And up until now, agencies without full-year funding, like the FLRA, have had to figure out how to implement the mandatory governmentwide pay raise, staff teams and plan for long-term projects without new money.

A spokesperson for the FLRA said in an email that in an attempt to stretch money, last year, the agency used end-of-year funds for some of its IT projects. If new money doesn’t come in, officials may have to defer spending on cybersecurity or other tech. For example, the FLRA wants to fully digitize its case filing system and achieve 100% electronic-records storage in the years to come, according to its strategic plan documents.

The other critical prong of the agency is its dedicated workforce, Grundmann said. Last year, the FLRA had 46% fewer full-time staff than it did in 2004, and there remain long-term vacancies in leadership positions, including the general counsel. With 60% of the federal workforce being represented in thousands of bargaining units, the FLRA is involved in ensuring disputes across agencies are addressed quickly and impartially to prevent disruptions.

“We talk about doing more with less, well, you can’t keep doing more with less and less and less,” Grundmann said, who was designated chairman in 2023.

While the agency has been ranked in the top 10 Best Places to Work in the Federal Government by the Partnership for Public Service, caseloads in some offices have increased by more than two-thirds in recent years. Even in its lean state, the agency has met or exceeded many of its targets for resolving cases quickly.

“Still, the longer the FLRA asks its employees to work beyond their capacity, the more it risks losing some of its most talented and productive workers to burnout,” a spokesperson said.

Grundmann said it is imperative that her agency’s work is not overlooked in budget discussions. For one, many cases require backpay for an employee who was out of work. The government may face liability the longer those owed wages are outstanding.

The FLRA also plays a role in resolving disputes before they escalate to arbitration, which can cost more than $7,000 per case, according to recent Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service statistics.

In 2023, there were 151 total arbitration cases.

Compared to other agencies that have similar missions in labor relations, the FLRA is the only body whose funding is below what it was in 2004, according to the agency’s figures.

“This is not a union issue,” Grundmann said. “It’s not a management issue. It’s a good government issue.”

Molly Weisner is a staff reporter for Federal Times where she covers labor, policy and contracting pertaining to the government workforce. She made previous stops at USA Today and McClatchy as a digital producer, and worked at The New York Times as a copy editor. Molly majored in journalism at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.