Federal employees are used to their jobs being at the whim of annual budget pressures and politicking, and they often work through whatever new crisis threatens the stability of government.

The potential for a default on the national debt, however, has been especially disruptive.

“The truth is we were flying blind,” said Randy Erwin, national president of the National Federation of Federal Employees, representing 110,000 government workers. “There was never a plan really articulated to federal employees or their union about what a default would actually look like ... they were frustrated by that.”

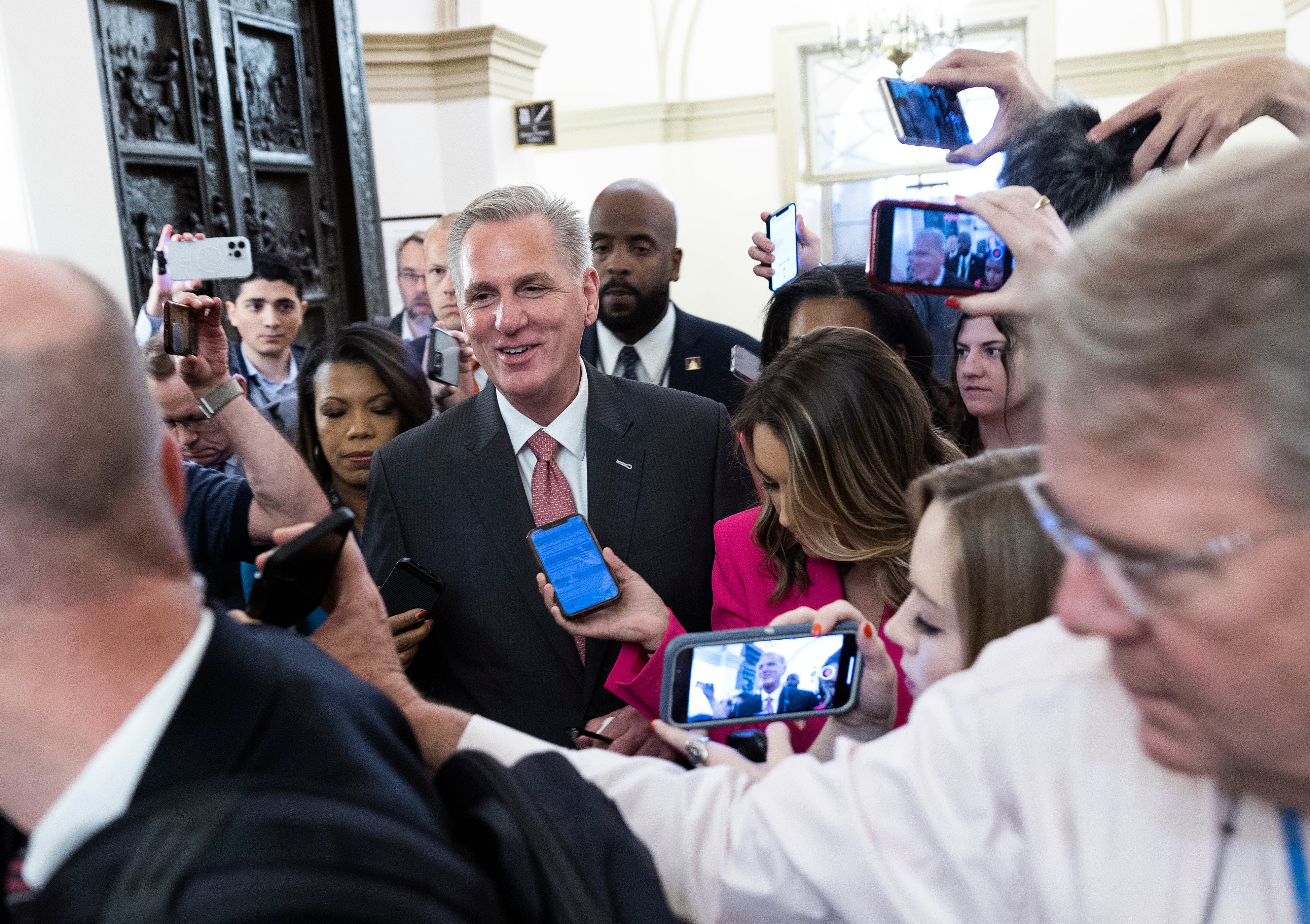

June 5 is the date to avoid a default, according to the U.S Department of the Treasury. President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy reached an agreement over Memorial Day weekend. The House is now looking to get votes passed as early as Wednesday evening on that agreement, which would raise the debt ceiling through 2025, flatten non-defense spending in 2024 and increase it only by 1% the year after.

Lawmakers urged spending caps on discretionary spending, which funds a number of things, including federal payroll. To assume that means federal pay will immediately be slashed is premature, experts said.

RELATED

“There’s nothing in this debt limit agreement that directly affects federal pay,” said John Hatton, who leads policy and programs at the National Active and Retired Federal Employees Association. The main challenge, he added, is that the spending limits under the bill are tight on the non-defense side, and negotiating with less wiggle room may put other priorities, like the amount of a federal pay raise, on the table.

However, it’s still the case that the President’s Budget for 2024 calls for a 5.2% pay raise and “the fact that nothing in this agreement changes that is a good sign.”

Once the debt impasse resolves and the normal appropriations process resumes, spending caps proposed for the next two years could indirectly affect the debate over federal pay in the appropriations process.

RELATED

There’s somewhat of a safeguard built into the agreement that creates an incentive for Congress to pass all 12 appropriations bills or accept a 1% across-the-board spending cut, which defense hawks will want to avoid. That helps guard against the potential for a shutdown and provides an incentive to pass full-year appropriations across-the-board, Hatton said.

For future pay increases, what’s guaranteed is impossible to predict, though that’s true of most years even without a budget crisis. If this budget negotiation produces something akin to 2013-era sequestration with different caps, then it’s possible there might be smaller pay increases.

“Next year could be tighter,” Hatton said. “If the expected pay increase comes out at 3% when spending levels are only increasing by 1%, it may make it more difficult to secure the raise for 2025.”

Ultimately, it’s likely to come down to a case-by-case basis for agencies depending on whether they received a surge in their 2024 discretionary baseline and how hard-hit they were by inflation.

RELATED

Effects for contractors

For the contracting workforce, things may look a bit different. Contractors could see payments delayed and contract awards or orders paused. If that happens, late wages and benefits could butt up against laws that require service contractors, for example, to make these payments in a timely manner or else be in violation of compliance.

“What is one of the strengths and most important requirements for all government contractors? It’s compliance,” said David Berteau, president and CEO of the Professional Services Council, to reporters on May 25.

Legal experts didn’t rule out the possibility that legal skirmishes between workers, contractors and the government could ensue if payments and benefits are tardy.

For the Pentagon, service members cannot be furloughed, but civilian employees can. And the Department of Defense “simply could not function well without its civilian workforce” should things escalate to that point, said Stephanie Barna, a lawyer at Covington and a former senior leader on Capitol Hill and in the U.S. Department of Defense.

Pentagon officials told Barna that they’re being told to keep coming to work until directed otherwise. Of course, the military would be required to work regardless. What’s uncertain is whether both civilian and military employees will be paid in regular order. If they’re not, that especially strains junior-level individuals and their families.

“Historically, people have been paid retroactively in the event of a government shutdown, but that’s small comfort if you’re waiting for a deposit in your bank account, and you’re an Airman First Class or a GS-12,” said Michele Pearce, former general counsel of the Department of the Army and lawyer at Covington.

Experts also said that the crisis shines a fluorescent light on cracks in government processes.

“Tradeoffs, for example, between personnel, readiness and modernization priorities are always difficult, even during a typical budget planning cycle,” said Pearce. “Striking the right balance during times of budget uncertainty makes it even more so. Do you choose between cutting personnel or delaying modernization programs? And what about readiness programs that ensure forces have the training and equipment needed to deploy?”

The message has been felt that government is willing to flirt with disaster, and that puts recruiting, retention, the remainder of the appropriations cycle and the industrial base on notice.

“It’s hard recruiting not only for the military or for public service, but it’s hard to ask people to dedicate their businesses and their innovations to the government, when the government doesn’t have the on-time funding required to be a constant and reliable partner,” Barna said.

RELATED

OMB urged to provide guidance

hatton said conversations with senior federal officials indicated that they are wading through this without clear guidance from the White House.

“What we know is there’s no common priorities,” Berteau told reporters. “There’s no common consensus. There’s no common objectives. There’s no consistency across those plans. That’s exactly what we saw happen in sequestration. Everybody had their plan. It just wasn’t integrated. It wasn’t coordinated, and it increased the negative consequences quite dramatically and extended the recovery period quite a long time.”

OMB did not respond to a questions about what direction they’re giving to agencies.

So, what can they do?

Agency heads are in a position to relay mission impacts related to delays across the legislative and executive branches, Pearce said.

“As we saw at the end of last year, there can be significant positive impact when leaders who have credibility with the Hill speak openly about how a lengthy continuing resolution will affect the soldier on the ground,” Barna said, adding that if a deal fails, operations will quickly get to an untenable place.

With reporting from the Associated Press.

Molly Weisner is a staff reporter for Federal Times where she covers labor, policy and contracting pertaining to the government workforce. She made previous stops at USA Today and McClatchy as a digital producer, and worked at The New York Times as a copy editor. Molly majored in journalism at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In Other News